Emoji Magic in JavaScript

Not all emojis are created equal. Some are more equal than others.

For the most part, emojis are the same in makeup. They are simply unicode character representations, much like the letters you are reading right now. And with over a million possible character representations your computer can render, there is quite a bit of space left after all the symbols you know, and all the ones you don’t know, for emojis.

With that great power comes an enormous amount of… emojis. So many that most people never even get to use the more special (or mundane) ones, and even more people have probably never even heard of some emojis.

And I’m sure nobody in the history of the world has ever heard of an emoji ZWJ sequence.

Yes, that’s right, an emoji ZWJ sequence. Say that five times fast.

So what exactly is this sequence? The shortest explanation is the code above. Notice how in line three, two emojis are joined with a space in the middle and this seems to create a singular emoji. Looking under the hood, this technology is not quite new, and far from magic.

Do the ZWJ

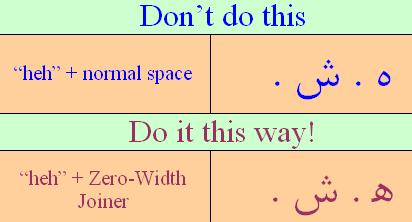

In Unicode, there is a character known as a zero width joiner (or ZWJ, pronounced 'zwidge'), represented by the code U+200D or ‍ . This innocent character isn't used much in Germanic languages such as English, but sees wider use in Arabic or Hindu contexts. There it is used to connect two separate characters into a singular character, hence the name joiner.

Source. Notice how the second symbol on the right looks different in each example.

The transformative nature of this character is really the driving point behind this behavior. Under the hood, this is not much more than a sequence of unicode. The specific sequence, if it corresponds to a separate symbol, will simply be computed to represent this special symbol instead.

In Germanic languages, we don’t really see this. All we do to form words is we put one character in front of the other, marking the end of words with a space or a punctuation mark like a period or comma. It can be a little hard to grasp these sequences at first. But emojis work pretty much in the exact same way.

Emojis

We saw that emojis are not much more than a single character represented by unicode. We also saw that there is something known as a ZWJ which can apparently combine unicode into representing new symbols. Now it’s time to put them together.

While some emojis are simple representations of single unicode, others are in fact combinations of them joined by the ZWJ character. We saw some examples already, but let’s look at some more examples and see what they look like under the hood.

🏳 + 🌈 = 🏳️🌈

U+1F3F3 U+FE0F U+200D U+1F308

Here we have a simple sequence of just two emojis, joined by the ZWJ character. The unicode above is the full unicode for the rainbow flag. Separately, the unicode for the other characters is U+1F3F3 for the white flag and U+1F308 for the rainbow. The other two characters aren’t visibly there, but they are required.

The U+FE0F code you see behind the white flag is called a variant selector. Variant selectors are not uniquely used for emojis, like with the ZWJ character, and there are 16 of them in total. This specific selector is, however, only used for emojis. This selector says that the emoji is to be displayed as an emoji, not text. You can reasonably infer that every emoji with this variant selector comes in both text and emoji form, which we’ll talk about more later. While it does not take up space, it does take up a character.

The U+200D is the ZWJ character we talked about earlier. This character takes up a character too. For everyday use, this may seem insignificant. However, pasting emoji ZWJ sequences into Twitter highlights a tangible consequence of both the variant selector and the ZWJ as invisible characters.

On the left, you can see that a simple emoji takes up just one character, and this makes sense: simple emojis (usually) comprise only a single unicode character, just like any of the letters in the Latin alphabet. On the right, is an emoji ZWJ sequence. Notice the difference in character count: we go from one on the left to a whopping six on the right. This is because this sequence is made up of exactly six unicode characters, viz. U+1F469 U+200D U+2764 U+FE0F U+200D U+1F469.

Breaking down the sequence Let’s break this sequence down a little. The sequence translates to ‘woman loving woman,' an emoji where there’s a woman on either side with a heart in the middle: 👩❤️👩. Knowing what we know already, we would expect this sequence to be comprised of three single emojis, and this is true. The first character in the sequence is ‘woman,’ spelled out it reads U+1F469. This is also the character at the very end, accounting for the two woman emojis. Next up is the ZWJ character, U+200D, and this one is repeated again right before the second woman emoji. That makes up four so far. Our third emoji, the heart, is U+2764, making five characters. The sixth character, then, is the variant selector U+FE0F. This character indicates that the emoji variant is used, not the text variant.

For the heart emoji, the U+2764 code is not enough to display a red heart. By default, using this code should render a black heart symbol, the text version of the emoji. If you want to make sure the text version is rendered, you can explicitly add the variant selector U+FE0E to the heart emoji code. These two variant selectors, U+FE0E and U+FE0F, are exclusively used to indicate which variant of the emoji to use. The former is also known as the ‘text variant,’ and these variants of the emojis are considered text. This is also the reason why the heart emoji is sometimes referred to as the black heart emoji. Mostly, U+FE0F is used in emoji ZWJ sequences where otherwise the emoji with a text variant can default to the text variant, and break the sequence in doing so.

Text emoji next to… emoji emoji.

There are other emojis with text variants, like the snowman emoji.

That’s why in the tweet box above, the character counter correctly deducts a whole six characters for just one emoji. There are in fact six characters that make up the emoji, even if you can’t see half of them and the other half have joined into one.

Funnily enough, combining emojis does not always work. While there is a list of supported emoji sequences (cf. infra), sequences don’t always translate into the desired combination on screen. The simple reason for this, is the operating system does not support the combination. The existing, official Unicode list is more of a suggestion for use to manufacturers. They outline which sequences are already in use, and so which sequences manufacturers should also support. But since this list is merely suggestive and not restrictive, manufacturers can simply choose not to follow the advice. Well, what happens then? The sequence simply does not get translated.

Suppose the rainbow flag is unsupported on Android phones. If we use the rainbow flag from a laptop or computer or iPhone, we would still see the rainbow flag inline. But Android users would instead see the simple emojis represented side by side, just as if we had used the plain flag and the rainbow emojis separately. This rarely happens today, and used to happen a lot more in the past. Nowadays, phones and other computers have a fairly standardized range of emojis and we rarely see double emojis where the author intended for a sequence to be visible.

Why do this

You might be asking yourself: why would anyone do this? Why not just create more simple emojis instead of combining them in this way?

As engineers, we don’t much like doing new work where old work will do just fine. In the same way, the emoji overlords can ‘create new emojis’ simply by pasting existing codes in a sequence. The creative possibilities of that are very appealing. Instead of needing to reserve extra unicode characters for new emojis, you can simply combine already reserved code in various ways. Above we looked at just a couple of these combinations, but these sequences are virtually endless. Think of it as combining components to form one larger component. If you’re familiar with Atomic CSS, that would be like combining atoms into molecules. The usefulness of an atom lies in its reusability. So if every new emoji is a simple one, they had better have some potential to be turned into a sequence.

Remember how we discussed the character count that unicode provides. It sits at a respectable number of over one million. But what if we want two million emojis? What if we want three million? What if we want a billion emojis? Current unicode limitations prohibit that, unless of course we get creative. Combining codes into sequences opens the door to having billions of emojis. More emojis than stars in the universe. Maybe emojis will be the new pollution. Too many damn emojis in the sea. But essentially a way of circumventing serious hardware limitations set forth by IBM and the gentlemen at the Unicode Consortium.

There are other reasons for this as well. When emojis were first created, they were only available to the operating systems that supported them. Invariably, these were also the systems that created them. This eventually created a monopoly of emojis where those with the power to display them, gained the customerbase. To combat this, the Unicode Consortium (not a made up phrase) decided to form the Emoji Subcommittee (also not made up) to unify and standardize emojis. This committee gathers twice a week for 45 minutes to discuss which emojis should make it into the official standard and which should not (I'm dead serious).

As is always the case, this standardization came with a set of rules. Rules on using emojis, rules on translating unicode characters and sequences onto the screen, and rules on what emojis should be. Today, there are rules on how to propose a new emoji for adoption into unicode. And while it doesn’t really say anywhere that new emojis have to be sequences, there is an underlying expectation of quality for the emoji to be singular enough in order to become its very own emoji. Your proposal for a new emoji must answer a whole line of questions about the emoji, some of these asking ‘can your emoji be represented by a couple of existing emojis instead’. If the answer is yes, then the committee would probably only accept the new emoji in the form of a sequence. For new simple emojis, there’s a question about its potential in a sequence. If there is potential, then that would seem to me to rule out the possibility of including your new emoji as a sequence. Careful planning, thought, and deliberation goes into each new emoji and the standards are very strict. It would seem that the committee are already aware of the problem of littering the universe with too many emojis, especially simple ones, and would instead prefer mostly new sequences instead.

The danger zone

Unfortunately, emoji ZWJ sequences are not all sunshine and roses. All the way back in 2015, there was a proposal to halt all adoption of new emoji sequences. The very first reason for this actually had to do with the use of the ZWJ character, itself. Since this character existed previously with an established use in certain language families, using it for this new purpose with emojis seemed unnatural. Additionally, there are concerns for now standardized keyboard and text editing behavior. The questions raised in the proposal concern problems with backspacing, deleting (referred to as forward-deleting, aka pressing the 'delete' button), and text selection generally. Advice at the bottom of the proposal included a comprehensive list of these sequences, which does in fact now exist. It also suggested no new emoji sequences be added, advice that seemed to have fallen on deaf ears.

Taking it back home, some programming languages seem to also struggle with emoji sequences from time to time. It is possible in JavaScript to spread each individual character into an array, or even join simple ones into sequences. But Swift, for example, doesn’t quite appreciate this party trick. Logically, if unicode characters are strings, they should return true if the proper parameter is entered through the ‘contains’ method, in this case the unicode corresponding to the character. Yet in a sequence, these simple emojis are paired with the ZWJ character, and so return false if you only look for the presence of the simple emoji in the sequence. Confusing stuff.

In the Julia programming language, emoji ZWJ sequences have kicked up dust too. When attempting to parse the rainbow flag sequence emoji, the parser actually threw an error since it did not recognize the ZWJ character. There, too, the question was raised whether or not the ZWJ should be separately identifiable or conjoined with the preceding emoji character in a sequence. It is unclear if this problem was resolved, the issue still being open on Github. But looking into the String type in Julia, uncovers additional complexity in handling emojis. Sadly, emoji sequences aren’t mentioned, but simple emojis are. Mind-bendingly, a series of three fruit emojis (banana, apple, pear) has a combined String length of five, despite only being three simple emojis. If you attempt to get the character at index 2 (Julia is 1-index based; the equivalent in JS would be index 1), you would get an error where you would instead perhaps expect either the ZWJ for banana or the unicode for the apple emoji. The resource provides a solution to this: it is apparently caused by byte based string indexing. Since the banana emoji is 4 bytes, the fifth byte is a space, and attempting to get the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th index for this character would throw an error. Thus attempting to get the byte based index of a string is directly related with the actual byte sizes of characters.

And you thought CORS errors were bad.

Take home points

Not quite fun and games, emojis. Some are more complex than others, being joined with either a variant selector or a ZWJ character. By their nature, they are a lot closer to low level programming: stuff like bytes, text encoding, unicode, and even binary. Though they seem innocent and innocuous, they can cause some serious hair-pulling, and indeed seem to have already done so in some programming languages.

Whether as a party trick to impress your friends--and finally get them to stop asking you to fix their printer--or as a more serious part of a not-so-serious hobby application or even development code, keep in mind that the emoji rabbit hole does in fact go very very deep. Simple, silly little icons they may appear, but pull back the veil and you may be looking at a series of foreign symbols and a whole bunch of ones and zeroes.

Resources

- Zero width joiner in Persian

- Emojipedia: emoji ZWJ sequences

- Text and emoji variant

- Meet the Shadowy Overlords Who Approve Emojis

- Emoji proposal guidelines

- Emoji ZWJ Sequence Considered Harmful

- List of standardized emoji ZWJ sequences

- Emoji ZWJ sequences in the Swift programming language

- Issue with code parser in the Julia programming language

- String type in the Julia programming language

- Jorge